On September 26, 2024, the Pennsylvania Nursing Workforce Coalition (formerly known as the Pennsylvania Action Coalition) hosted a successful and engaging breakfast at the 2024 Pennsylvania Organization of Nurse Leaders (PONL) Annual Leadership Conference in Harrisburg, PA. The pre-conference event marked the unveiling of the PA Nursing Workforce Coalition’s (PA-NWC) new strategic plan and the introduction of its key initiatives, aimed at advancing the nursing profession in the state.

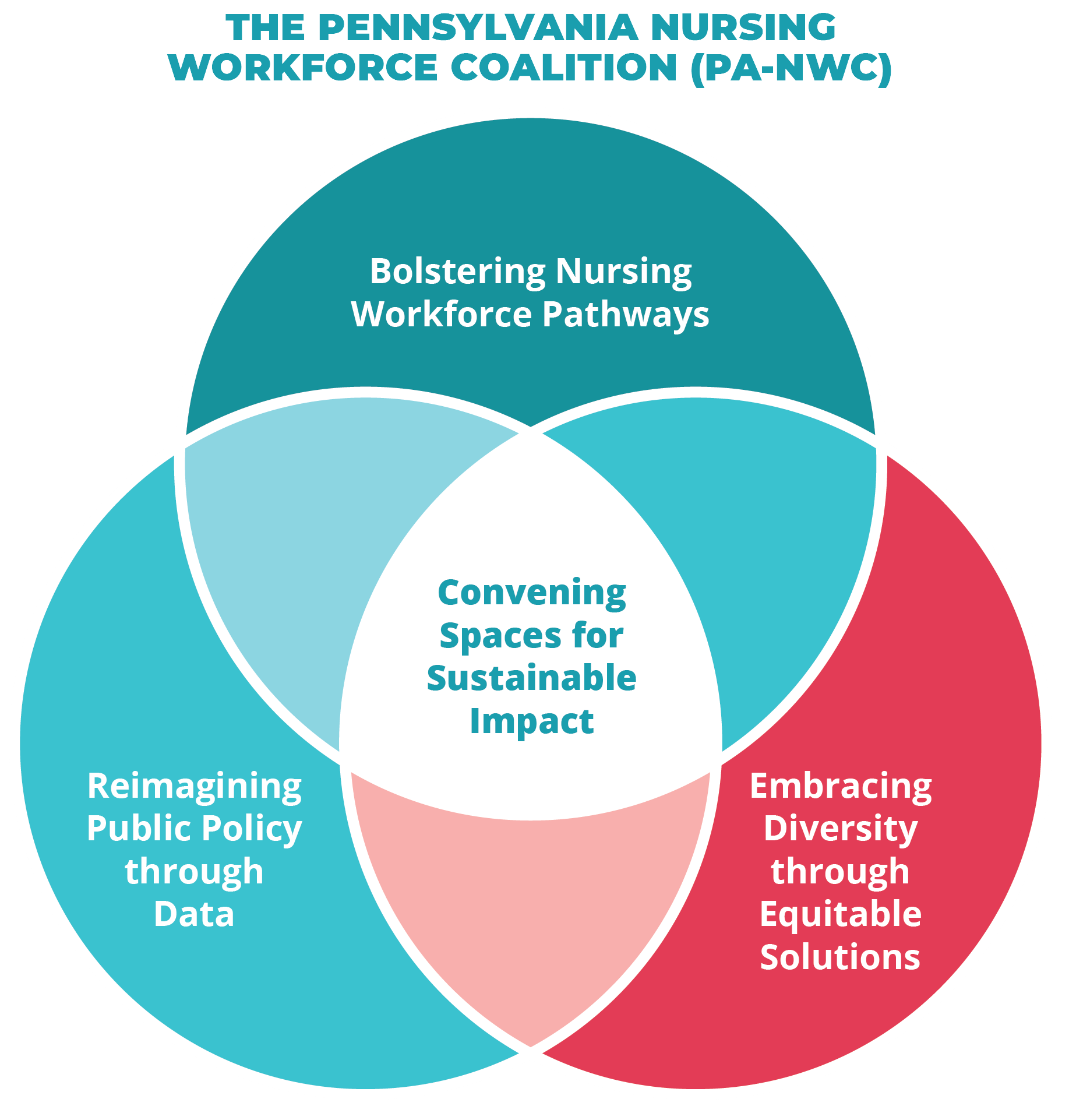

The breakfast event featured a presentation from the PA-NWC Team that informed and inspired attendees, with a strong focus on the PA-NWC’s new strategic direction. The PA-NWC emphasized its commitment to three major initiatives:

The presentation received positive feedback, with participants finding the information valuable and relevant to their professional practice. The variety of speakers and perspectives contributed to a well-rounded discussion.

A highlight of the event was the interactive roundtable discussions, where attendees shared insights and ideas to enhance the Coalition’s initiatives. Roundtable discussion topics included:

Reimagining Public Policy through Data: Attendees discussed ways to integrate nursing into public policy by creating annual “state of the state” reports and expanding engagement through community events like health fairs and schools. Ideas also included introducing policy education to nursing students and mentoring leaders to run for public office, ensuring that nursing professionals play an active role in shaping policy.

Bolstering Nursing Workforce Pathways: Discussions focused on strengthening the nursing pipeline through youth engagement programs, such as Geisinger’s Aim HI and Allegheny Health Network’s Young Scholars. Participants emphasized the importance of providing financial support, internships, and clinical opportunities to students, while also addressing barriers like limited rotations and nursing school closures.

Embracing Diversity through Equitable Solutions: Roundtable discussions emphasized the need to build a diverse and equitable nursing workforce. Attendees highlighted the importance of engaging underrepresented communities through local organizations, schools, health fairs, and churches to raise awareness of nursing careers. Mentorship was also seen as key, with participants advocating for more support for individuals from diverse backgrounds in nursing education and practice.

Suggestions included partnering with academic institutions to create programs that support underrepresented students and offering scholarships, internships, and financial support to attract diverse talent. Participants also noted the need for inclusive environments in both educational and clinical settings to retain diverse nurses.

Suggestions included partnering with academic institutions to create programs that support underrepresented students and offering scholarships, internships, and financial support to attract diverse talent. Participants also noted the need for inclusive environments in both educational and clinical settings to retain diverse nurses.

Networking and collaboration were central to the event’s success, with many attendees expressing that the interactive and community-driven format allowed for valuable exchanges of ideas. The Q&A session sparked engaging discussions, further enhancing the event’s impact. Overall, participants felt the event provided not only valuable insight into the PA-NWC's future but also a forum for fostering connections and advancing the collective goals of the nursing profession.

SARAH: Sarah, this is At the Core of Care, a podcast where people share their stories about nurses and their creative efforts to better meet the health and healthcare needs of patients, families and communities. I'm Sarah Hexem Hubbard with the Pennsylvania Action Coalition and the Executive Director of the National National Nurse-Led Care Consortium. On this episode, I sit down with Donna Bailey, the CEO of Community Behavioral Health or CBH. They're the organization that pays for behavioral health treatment for Medicaid recipients in Philadelphia. We'll discuss how CBH supports mental health care and access to resources for many Philadelphians, and specifically how that support reaches people who are pregnant and parenting.

This conversation builds on some of our earlier episodes, where we talked about a mental health collaboration that NNCC developed with Joseph J Peters Institute or JJPI. Through that work, we've been able to support more than 200 clients who are pregnant or parenting young children to connect with therapy services. We've been able to sustain this type of community-based integration, partially because JJPI is part of CBHS provider network.

As you'll hear throughout this episode, access to mental health treatment is all about meeting people where they are and even engaging them in services before they need them. When it comes to systems change, we'll talk not only about innovations in overcoming barriers to treatment, but also, the social structures that impact mental health and well-being. What we know is driving most mental health concerns the social determinants of health.

Before we turn to my conversation with Donna, it's important to note that we're bringing you this conversation to coincide with black maternal mental health week, which this year 2024 runs from Friday, July 19 through Thursday, July 26

Donna, thank you so, much for making the time to be here today to have this conversation before we dive in. I just wanted to hear a little bit from you about what led you to get into community health and public health more broadly.

DONNA: Hi, Sarah, it's so, good to see you, and I just want to thank you for reaching out to give me this opportunity to highlight all the good work that's happening at CBH, and also, to highlight black maternal mental health week. So, in terms of my career in public health, to be honest, I have to say, this isn't the career that I envision. I was definitely off on a track for corporate work, and had actually worked at Johnson and Johnson for a little bit after I got my MBA. So, I like to tell people that this work really chose me, and I'm really grateful for colleagues and mentors who recognize my potential to serve and make a difference in this sector. So, sort of life circumstances, geography, I moved around for a little bit, and once I landed back in Philadelphia, decided that I was going to go get a second master's, this time in psychology. And so, after I got that degree, I started to work at nonprofits here in Philadelphia, did a lot of direct service work, kind of went up the trajectory and that ladder, and then realized that I could potentially be more impactful at the systems level. So, I got involved in government, and through that work, in 2013 landed at CBH for the first time. And so, I would say, through all of those sort of twists and turns, the common theme has been really being involved in work that it had an impact on health and wellness for Philadelphians.

SARAH: We'll definitely want to circle back to different components of your experience. But I think before we go any further, can you explain to the listeners what is CBH.

DONNA: Absolutely. And you know, we do have a little bit of an identity crisis. Our name in itself, kind of suggests that we do direct services, and we don't so, CBH, or community behavioral health, is the Managed Care Behavioral Health Organization for Philadelphia. So, what does that mean in Pennsylvania, insurance for people who are on medical assistance is managed care, and it's in a program called health choices. So, whether it's a physical health MCO, or behavioral health MCO. It's all a part of the managed care system called health choices in Pennsylvania. And so, when Pennsylvania decided to go the managed care route, counties were given the right to determine how they were going to administer the program, and Philadelphia was the only county to decide that it was going to create its own entity. And so, they created CBH. What makes it a little bit interesting is that we're not government, but sometimes we are. The actual structural relationship is that we are a nonprofit. We're a 501, c3 under contract to the city of Philadelphia to administer the program. And so, where we actually sit? Within city government is within the Department of Behavioral Health and intellectual disability services. So, the state contracts with the city through DBH IDs, and DBH IDs then subcontracts with CBH. And so, our sole reason for being is to ensure that for Philadelphians, and again, we're pretty unique in that the work that we do is only for Philadelphia. For Philadelphians, our objective is to ensure that we have a robust network of providers, whether it's independent practitioners or the big hospital systems and everything that falls in between, to provide services mental health, substance use disorder, autism services, the whole array, we are required to provide access to members who need those services. So, we maintain the network. We do quality work, compliance work, fraud, waste and abuse, all of the things that you would typically think that your physical health NCO would be doing. We do it. What makes us a little bit different and a little bit more interesting, and I think special, is because of where we sit in our relationship to city government. We have really strong partnerships with other health and human services organizations in the city, like DHS, which is child welfare, like the health department, like homeless services, and what we find is our members, our CBH members, our beneficiaries, are involved in multiple systems in Philadelphia. And so, through our work with these other systems, we're really able to treat the entire person. And so, these days, you hear a lot about social determinants of health. That's really what those other human services organizations are focused on housing, childcare, food access, pairing it with behavioral health really allows us to touch on all those things that really impact one's wellness. So, that's kind of what we do.

SARAH: Thank you so, much for laying that out for us, and you're right, it is complicated, but I'm definitely hearing some areas of opportunity in that structure. And you've been at CBH in your current role as CEO for about eight months, and then you were there several years before, but recently, and I know this from having the opportunity to work with you there, you were also, at Public Health Management Corporation for a while as well. How do you feel like your time doing some of that integrated health services work has impacted your return to CBH?

DONNA: That's a great question, and folks have asked me that as well. Even folks here at CBH are interested in what the lens is that I look through this work now, having had the experience at the provider level, but yeah, I was at CBH for about eight and a half years. I mostly served as the COO and then in 2019 when Joan Arnie was retiring, I was appointed the interim. And early in 2020 the world as we knew it changed, and we all pivoted, and remote work and telehealth, and all the things that we were able to dial into really allowed CBH to work with providers to maintain access. And so, during that time, I was thinking about what I might want to do next in my career. And I'll be honest, what I was really excited about when I was contemplating PHMC was the work that PHMC was planning at the Public Health Campus at Cedar, in collaboration with Penn and with IBX and with CHOP. And so, I started at PHMC in late 2020, as you said, as the chief integrated health services officer, and it felt like the lion's share of the services portfolio. So, I had all of the behavioral health and all the primary care services, and really my role was working with all of the leaders in those portfolios of work to figure out how we could streamline accessing services and receiving services for the member experience, so, that it wasn't disjointed or people weren't having to repeat things at intake. How do we look at the whole person no matter what service you're receiving? So, I think one great way that we were trying to do that was building out this Public Health Campus. And so, we had the federally qualified health center there, we had dental there, we had some of the other behavioral health programs there. And I think it also, stands as a really neat way to systemically begin to address health disparities. We know that that was the old Mercy Hospital that had closed, and there was a deep need in the community for services. So, really excited to have been a part of that project. But I will tell you I got, I think, a renewed sense of what some of the challenges are at the provider level, and particularly for direct care staff. And let's remember, many of us were able to work from home during those years, but folks who were tasked with actually meeting our members, they never stopped, you know, and telehealth was great, but for the most part. Start many services still occurred face to face, so, developed a real appreciation for that work, but also, for the work that organizations had to do in terms of envisioning what the future would look like, especially as we were coming out of covid and some of the resources that were available through the loans and other type of resources from the federal and state governments. As those were ending, agencies were really having to rethink their organizational structure, their capacity. You know, how people like to receive services was shifting. So, we were seeing drops in service utilizations, and all of it ultimately impacts the bottom line. I know we don't like to talk about dollars when it comes to health care, but it's certainly a primary component. And so, for me, I developed a real appreciation of what it takes to sort of manage the delivery of services at the provider level. So, I've brought that back here to CBH. And one of the things that we've really been trying to partner with provider organizations on are, you know, we ask for a lot of things administratively, and some of the things we're required to do, some of the things we ask for because we have an interest, we like to do surveys. So, we've really been trying to be thoughtful about, what are the things that we have to require of providers, because the health choices program requires it of us. What are some things that are informative and we should continue to ask for, and what are some other things that we really could dispense with? So, we're having those conversations with organizations, and I think they've been really fruitful. But for the most part, I'm really trying to reset the relationship that CBH has with the provider network, I really want it to be focused on transparency and accessibility.

SARAH: It must also, be really interesting coming back to CBH in this kind of returning into a different climate, a different atmosphere. And when you spoke about the government programs that have been dialed back over the years, we see that in the client and patient or member population as well, that potentially, some of the resources that were maybe lifting folks up during the pandemic are starting to go away. How is that playing out in the design of services right now at CBH looking to sort of the overall welfare of the community that CBH is serving.

DONNA: You know, there are services that we are required as a behavioral health managed care organization to pay for, and it's the gamut. I will say, a component of what we do in our provider operations portfolio is network adequacy. So, we're always looking at data to understand what utilization looks like in a particular level of care, and do we need more of something or less of something? And again, those are conversations that we have to have with providers as well, because we do believe there needs to be a resetting of the network generally. To your point that things are changing out on the provider landscape, some agencies are going to make the hard decision that they're going to close a program or reduce a program. So, we're working hand in hand to kind of figure that out. But I would say generally, we feel like we have an adequate network now. There are some services, and you know this, Sarah that there's always more need than capacity, particularly for children, and particularly for children who have autism. And so, for those services, we have what we call an open network, meaning any willing provider who can come forward and has been licensed and credentialed, we're willing to have you in as an in network provider. So, we're constantly looking at the data. We're constantly talking to providers. Increasingly, we're talking to members, so, we're creating additional opportunities to engage with members. We're going to be introducing, in the new year, a two-way texting program where we can follow up with members after services, to get a pulse on how did you like your therapist? Did you get in in the time that you thought you were going to get in? Tell us generally, what your thoughts are about your healthcare, and we're doing a lot more member education out of our Member Services Department.

SARAH: I'm glad you brought up network adequacy, because sometimes when we talk about access to mental health, people think about wait lists, but we know access is so, much more than that, and there are many reasons why people might not have meaningful access to treatment or just to the resources they need for good mental health. Can you provide some examples of how CBH is addressing access to mental health? And you know, once we've established network adequacy, what are the barriers, and how do we address those barriers?

DONNA: Sure, and I would say it's really all of those social determinants of health, transportation being a very basic one, child care, you know, if you don't have access to consistent and nutritious meals, the last thing you're going to be potentially thinking about is therapy. So, really, those basic, basic things that you need to just function. And so, one of the things that. We've been doing here over time, and I'm happy to share some of those with you. Today is really trying to meet members where they are. Our primary focus is offering member centric, integrated care. We have developed what we call our community-based care management teams, and that's exactly what the name says community. So, it's my trained clinicians, not working within the walls of 801 market, but being embedded in OBGYN clinics and children's hospitals and primary care clinics and federally qualified health centers. And again, they're not delivering services because we are the insurance company, but they are partnering with those community-based organizations and those primary care organizations to do a number of things, one education, because there's still a lack of understanding and a lot of stigma around mental health. So, they're there to educate the staff as well as patients. They're there to provide resources, referrals, linkages, and then they're there to actually talk to the members, you know, what are you needing in your life, to provide stability, to support your mental health? And then they can work with those organizations, with community-based organizations, with some of those human services agencies that I mentioned, to help navigate and to make those connections. And so, our overall goal for these community-based care management teams is really to reduce barriers address health equity, because we know underneath all of this is health disparities and health equity and really mitigate some of the social determinants of health barriers.

SARAH: That's so, essential in terms of reaching populations as a whole, and I know that we see this particularly in the perinatal population. I'm wondering if you could tell us a little bit about some of the initiatives that CBH is doing to reach that population.

DONNA: Sure. So, we have our integrated perinatal community care team, and they work specifically with this population, really as a preventative measure. And so, we know that women who are pregnant, women who are postpartum, are at high risk for anxiety, for depression, for a sense of isolation and feeling overwhelmed. And so, we wanted to work with other systems and with community-based organizations to try and get ahead and support women before any of those negative outcomes would happen. And so, this team is embedded in OBGYN clinics across the city, and essentially they are there to really walk folks through here are all the things that we could offer you, in collaboration with a food bank, with your primary care, with child welfare, and help them navigate those systems. One of the other really neat things about this team is that they have certified peer specialists embedded in the team so, women who have experienced some of the depression and anxiety that comes with being a new mom, and who have been a part of some of the human services systems and have had to navigate on their own, they bring a wealth of first hand information of all the things that they've learned along their own journeys. I would also, say another really neat feature of this team is that we have a pharmacist attached. And why that is important is oftentimes women are apprehensive to take medication when they're pregnant, specifically psychotropic medication for mental health disorders. So, the pharmacist is there to provide education, to work with the OBGYN to provide education as well around what medications might be safe based on the woman's health profile at that time. And we also, have a physician advisor, attach who is a psychiatrist who works in concert with the OBGYN. We've gotten great reviews about how this team has been collaborating in the clinics. We'd love to be able to expand, but we want to do some level of assessment, some lessons learned, be able to scale up strategically and thoughtfully. I'm really excited to report that since this program started in March 2022 we've worked with and enrolled almost 800 women, and what that means is that they've worked with our teams, and then refer to social determinants of health, communities, organizations or other organizations that meet their needs. So, we're really proud about that.

SARAH: Mental health is so, broad. We all know that it encompasses so, many things, what kinds of resources are available for parents who are experiencing substance use problems, and what kinds of services and resources are out there.

DONNA: I would say, even prior to the pandemic, CBH had really focused on reducing barriers to substance use treatment. Specifically, we knew that we were the epicenter of the opioid epidemic. Even today, Kensington is very much a focus of this administration. One. And so, we did a number of things, beginning in early 2020 late 2019 one, we eliminated any and all administrative barriers to getting into treatment. There's something in insurance called a pre authorization for services, so, to call the insurance company to get approval, we eliminated that for all substance use treatment programs. So, essentially, someone could show up at one of our crisis response centers, and in Philadelphia, those are typically the entry points for treatment, show up, be assessed, and be able to move right into a treatment bed, or show up at a substance use outpatient clinic and be able to start treatment right away. So, that was key, eliminating those barriers in terms of treatment beds Since 2020, we've also, brought up over 200 new beds again to make sure that we had capacity. I mentioned the certified peer recovery specialist. We worked with our state partners to make that a Medicaid billable service, and that's really important to be able to have Medicaid pay for as many services as we can. We've embedded certified peer specialists in ers and the crisis response centers, and we've done a lot of work with providers in particular to make sure that they haven't created any barriers to treatment as well, and so, we've asked them to look at their operational flow to make sure that people are getting through and getting the treatment they need as quickly as possible. We have 15 programs that are specific to women or women and children, which is really important to keep families intact. I want to call out a PHMC program, Interim House West for women and their babies, where they can get their treatment. They can study for their GEDs. They have groups. There's childcare on site. And so, we are really supportive of those types of programs that are treating women by keeping families together.

SARAH: And does that relate to Mommy's Helping Hands?

DONNA: Absolutely. Mommy's Helping Hand is another community-based care and management team specifically for women who are struggling with substance use disorder. That team is really tasked with coordinating care on their behalf, helping them schedule doctor appointments, education, connecting them to community resources, and just being that additional resource for a question, or how to navigate, how to get reconnected to a substance use treatment provider. You know, I've been disconnected, and I can't get an appointment. Can you help me? So, that's just another sort of tool and the toolkit specifically for this population.

SARAH: So, how does that look? I mean, how do you find these moms, or find folks that would benefit from this program?

DONNA: For mommies helping hand in particular, we don't contract with specific agencies. It really is outreach and engagement that our team does, so, they're cold calling agencies. Do you have someone who has this need? They do a lot of education with providers. We have oftentimes big provider meetings. They'll come and do a presentation. So, it's really us assertively outreaching to agencies that are in our network, other community-based organizations, really marketing this resource and this service.

SARAH: You spoke earlier about telehealth, and certainly, I think we all know the pandemic blew up our notions of telehealth and really rethinking access. So, I'm curious, you know, from your perspective, what does the future for telehealth look like, and also, what are some of its barriers? What are its limitations?

DONNA: Telehealth was really a godsend during the pandemic, and I have to say that our partners at the state really acted quickly and collaboratively to ensure that from a managed care organization, we were able to offer that as a resource. Even in the beginning, it was telephonic only, which is typically not allowed, and so, over the course of the years, telehealth has really been cemented as an option that we can all use to ensure that we maintain access. As a matter of fact, just this week, a bill passed in the Pennsylvania legislature really requiring managed care and commercial health plans to cover telehealth. Now, of course, we've been doing that here at CBH, but this is really a win for people who are medical assistance and people with commercial insurance. We were really delighted at that news. Now, I would say telehealth is not a panacea for everybody in every situation. Definitely was incredibly helpful when we couldn't be face to face, and there's certainly times when it makes sense. So, we talk a lot about transportation, But transportation is a very real barrier for a lot of people, and can make the difference between making the appointment or not so, great. In that instance, great when you don't have a couple of hours to try. Travel, but you could find a private space somewhere and do a telehealth appointment. But it also, has its downsides. There are times when therapy is more effective, when you can have that face-to-face contact. And so, for us, we are really looking for choice number one, that members have a choice, but that providers are offering the option, we get a little concern if we hear that a provider is not offering any telehealth and everything's in person, or they're only doing telehealth, and so, we're really expecting a balance that meets the needs of that agency's particular membership. I would say the other thing is that oftentimes, if you're trying to do a tele health appointment at home, and you're a mom and there's kids around, that could be distracting as well, and so, so, many different scenarios when it's the right thing, and at other times, an in person would be more effective.

SARAH: And centering that on the consumer's preference makes so, much sense. And I know we also, hear issues related to language access and even safety in the home, and really needing to make sure that we're meeting people where they are, wherever that is. So, this episode will drop during Black maternal mental health week in July. We know that an estimated 20% of new mothers experience a mental health issue, such as postpartum depression, but for black mothers, the incidence is much higher. One study found that it was up to 80% higher in a study focused in rural areas and small cities. But we would anticipate, I think, that being true here in Philadelphia as well. It's similar for a pattern of trauma exposure. So, a study that found trauma exposure to be the highest among black women, 87% for other women, ranging from 29 to 74% so, given that also, looking at associated risks, such as substance use disorder, seems really important that providers are recognizing the specific trauma that black women have experienced, and are continuing to experience, especially our perinatal population, that the instances that we're seeing so, much documented in the delivery of care. How is CBH looking at this issue and looking to address disparities in mental health for black women in particular?

DONNA: I want to start by just echoing what you said. So, we know that black and brown communities are disproportionately impacted by healthcare disparities, and I think if nothing else, covid illuminated that our members who are in medical assistance face many disparities just due to their address or their geography and some of the barriers, like we talked about, education, transportation, childcare, food, all of those things. I can tell you that over 30% of our eligible members reside in North Philly, the lower northeast, Southwest and West Philadelphia, and we know that those are high need communities. These communities have the lowest life expectancy and the highest rates of poverty, homicide, infant mortality, drug overdose, all of those things. And 2022 of our membership, 75% identified as black or Hispanic. And so, that just gives you some grounding in terms of who our members are. 11% use a primary language other than English. And so, it's incumbent upon us, as the managed care organization, to really infuse a health equity lens, a DEI lens, through all of the work that we do. And we've done that in a number of ways. One, we just polished off our three year strategic plan. And so, the three main pillars are a people first culture, and that's for our members and our staff, whole person care. We've been talking a lot about that, particularly through our community-based care management and driving organizational excellence, being efficient, driving quality, being good fiscal stewards. All of this work has been infused with a DEI perspective. One of the things that we really committed to back in 2022 was obtaining a multicultural healthcare distinction. And we did, and that's an accreditation that's awarded by the National Committee for Quality Assurance. It's a gold standard in healthcare. So, we got that, and right now we are preparing for NCQA healthcare equity accreditation, which is similar, but a little bit more robust, and generally speaking, we also, have NCQAs Managed Care accreditation. These processes are really vigorous, and they cover everything from your policies and procedures and your hiring practices to your network capacity and your network demographics. So, it really forces you to look at where you potentially have some gaps and address those. And now in 2025 we're going to be going after health equity accreditation. And why that's important is because the rigors of obtaining those. Accreditations really force the organization and everything that it does, from its policies, procedures, its hiring, its recruiting, the composition of its provider network, to really have DEI and health equity infused across all of those things. So, I think it's really important to start with how we function as an organization being the basis through which we are going to address health care disparities, particularly for black women and black parenting and postpartum women in particular. So, we've done that work, and are continuing to do that work. We're also, working with our provider network, because they are the people who are actually directly interfacing with members. We are requiring all of them to train their staff and cultural competency, and that's going to be a lift. We'll have some conversations about timelines and how we can support that. We also, think that's a very important investment to make. We are also, really focused on meeting members where they are. We talked a little bit about that through some of the care management strategies, but you also, have an initiative that we're kicking off in July that we're really excited about. It's called the hair initiative, and that stands for Health Access Initiative for Recovery. And what we're doing with this pilot is we are training up barbers and stylists in the north Philadelphia zip code, where we've seen a spike in overdoses. We're training those stylists and barbers on how to talk to their clients about mental health, about depression, about anxiety, about, you know, my child is experiencing this, and so, we're going to train them and some key components of how to have those conversations in a trauma-informed way. We're going to equip them with resources. They'll have our Member Services number which I have to put a plug in for. One 888, 545, 2600 operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week. We see stylists and barbers as a really important component of the Black and African American community, and so, it's a way that we're really trying to partner, get folks trained up and be able to have those conversations in a way that's less diagnostic and less stigmatizing and more welcoming and just coming from a space of relationships. You know, people have relationships with their barbers and stylists, so, we're starting it off as a pilot, but we're hoping to scale that up throughout Philadelphia. I think that's important to say, not everybody needs treatment, but we all need a touch point on how we're feeling and how we're doing, and if we need some additional assistance in something which who doesn't from time to time.

SARAH: You know the innovation that you're describing right now lends insight, even in terms of how we talk about workforce, this idea, we really are all in it together, and there are so, many ways that we need to be addressing the mental health of a community, through prevention, through treatment, but we also, know that many provider organizations have been struggling to retain their workforce, and this is certainly not limited even to the mental health profession. We see that in childcare. Certainly, see it in nursing. So, how has that been looking in Philadelphia? Are you seeing any promising strategies to support it? What are your thoughts on our workforce challenges?

DONNA: Yeah, yeah, it's really challenging. And I think that specifically for the behavioral health sector, we've seen people leave the field altogether. It is extremely hard to hire a psychiatrist right now and forget about finding a child psychiatrist. We've seen direct care staff leave the field and go work in retail or some other space. And so, it's pretty dire, and it's one of the reasons that we're hearing from providers that their businesses are being really impacted, and it's impacting access. If you don't have staff, you can't deliver the service. And everybody's feeling it across the board. And as you said, across sectors, I think in a city of EDs and meds, it's really incumbent upon us to think about this strategically and for the long term. You know, I wish there were some quick, easy answers, but I think that this is a long haul strategy, starting with really professionalizing the work for direct care staff, in particular, these are often the lowest paid people who are doing the heavy lift and who have their own trauma and are potentially experiencing trauma through the work that they're doing with the people they're supporting. And so, professionalizing the work, embedding in supports for health and wellness of the staff. And then I think, How can we look at what's actually needed for a particular position? We have these conversations here at CBH all the time. I'll look at a job description, and we're asking for five levels of credentialing, and maybe we only need two. And so, I think it's taking a step back. We never want to compromise quality. Right? But I think we need to think differently. You know, maybe there's opportunities for somebody who is new out of school to do their training and still work, you know, and gain those supervision hours, why they're actually working, you know, looking at growing the pipeline through internships and partnerships with the schools, and I think providers working together. You know, sharing staff is not something that we typically think about doing, but is that something that could work? I think it's longer term, but I definitely think it's the time where we need to sit down and really start coming up with some concrete next steps.

SARAH: So, this could be related to workforce, but certainly related to any of the issues that you've talked about. Are there things that you're looking to government to support, whether that's at the state level, federal level, what kinds of systems change could help support some of the promising practices that you've been describing?

DONNA: So, I again have to give a shout out to our partners at the state in particular, Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, or PA DHS, they recently submitted what's called an 1115 waiver. It's called bridges to success, keystones of health for Pennsylvania. And what that would do is allow for Medicaid to pay for things that address the social determinants of health. Right now, we pay for treatment, but this waiver would allow Medicaid-managed care organizations to pay for child care, to pay for services for people when they're what we call behind the walls. So, when people get incarcerated, their coverage stops, but this would allow for that coverage to continue and for transition planning post-incarceration, it would pay for food. It could potentially pay for continuous coverage for kids. So, we are really excited. We've done a letter of support. We believe that this will ultimately be approved by CMS. I think what we're very interested in understanding is the logistics and how it gets operationalized. And so, even in our regular business, we often see some of the smaller agencies really struggle with the rigors of Medicaid billing and the infrastructure around that. So, I think we're very curious to understand how the federal government and the state government will support those communities organizations or provide pass through organizations to help them with the Medicaid side of it. So, we're super excited about this. This is a game changer.

SARAH: So, Donna, as we had talked before, I mean, you really only been back eight months, not even a year. What are you most excited about? Obviously, the Medicaid waivers coming through would be an incredible opportunity for the state. What's exciting you know, for your team at CBH, for things on the horizon in Philadelphia,

DONNA: I'm really super excited that I'm not managing through the pandemic. The last time I did this, it was covid all day, every day, and so, to come back where we're not in crisis mode has really been nice, and I can actually engage with staff directly and not on Zoom every day. So, just from a personal and professional perspective, it's nice to be back at 801 and to see people and have all staff meetings and do things that are fun and encouraging for our team, we have an incredibly talented, dedicated group of people I work with the best leadership team ever, aside from my colleagues at PHMC. It's been really nice being back and being in this work that I think is so, impactful right now in this moment where we are but I think things like the hair project, working with partners to come up with other really innovative things that are not a heavy lift and are not a big financial spend, and people already have ideas. And so, one of the things we're trying to do is not have this be a top down organization, but really encouraging creativity and innovation across the organization. One of the other things I'm excited about are some of the changes that are happening within city government. So, right now, many of the commissioners are acting or interim, and so, there'll be people who will be remaining in those positions. It's always really exciting time to see what the vision at the higher level is going to be and what role CBH can play in having that vision materialized. So, really excited about that as well. Another thing that I would just flag is that we don't do this work in a vacuum. There are other managed care organizations across the Commonwealth that we have really strong partnerships with, and so, we can pick up the phone anytime and say, this is happening in Philly. What are you seeing? Or you did this program? We're thinking about standing it up here. And the hair project was actually one that was started by Community Care Behavioral Health, and so, they really partnered with us. We're using the consultant that they used. So, really excited about those things, but I think overall, what excites me most is having the opportunity to. Work with the team here to have CBH be the best managed care company we can be all of those metrics that we're measured on. I want us to have really excelled in those areas, because ultimately what that means is good quality, accessible care for our members. We have a lot of different metrics that could make your eyes glaze over, but ultimately, when we do well, that means things are happening well out there on the front line.

SARAH: This has been such a fantastic conversation. Thank you so, much for making time to share your expertise, and really, I'm just excited to see where things go from here.

DONNA: Thank you so, much for having me. It's always so, good to talk with you, and I just appreciate the opportunity to talk about all the good things that we're doing here in Philadelphia and at CBH and within our provider network. So, thank you.

SARAH: Thanks again to Donna for making time for this conversation. Thank you also, to the van Ameringen Foundation for your support to help raise awareness around access to mental health services. You can find our most current and past episodes of at the core of care, wherever you get your podcasts, or at pactioncoalition.org on social media. You can stay up to date with us through our handle @paaction and @nurseledcare. This episode of At the Core of Care was produced by Emily Previti of Kouvenda Media and mixed by Brad Linder. I'm Sarah Hexham Hubbard with the National Nurse-Led Care Consortium. Thanks for joining us.

We are excited to announce that as an outcome of the thorough strategic planning process that we engaged in over the past several months, we have a new 5-year strategic plan and we will be refreshing our brand as the Pennsylvania Nursing Workforce Coalition (PA-NWC).

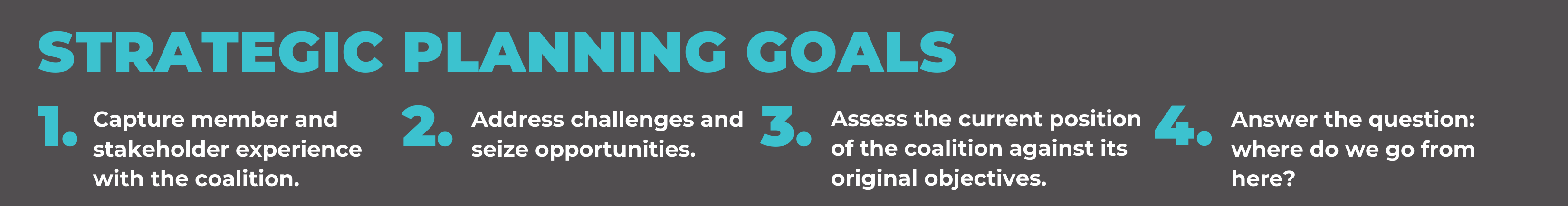

When we embarked on this process, our goals were to:

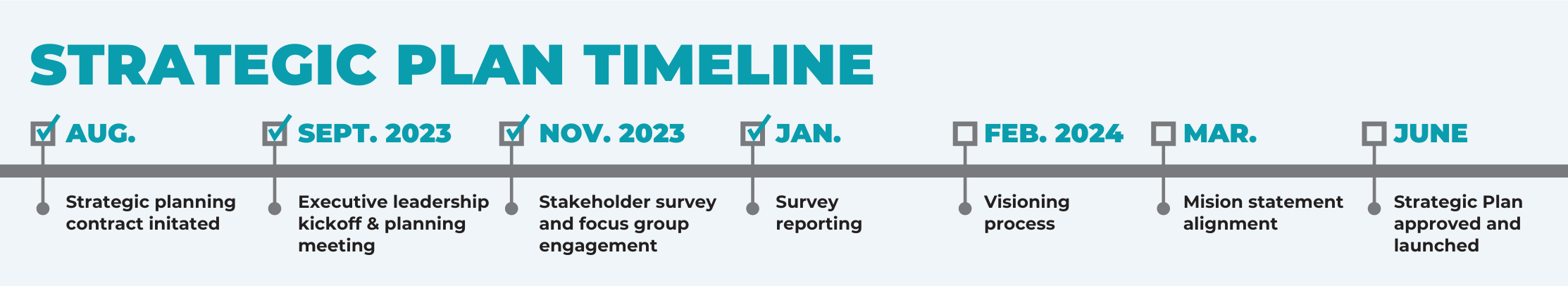

In the summer of 2023 we hired Generative Consulting Partners to guide us and we created several opportunities for engagement from our Advisory Board and stakeholder base. This included a survey, virtual focus groups, visioning sessions, and in-person meetings. Please find a synopsis of the feedback below:

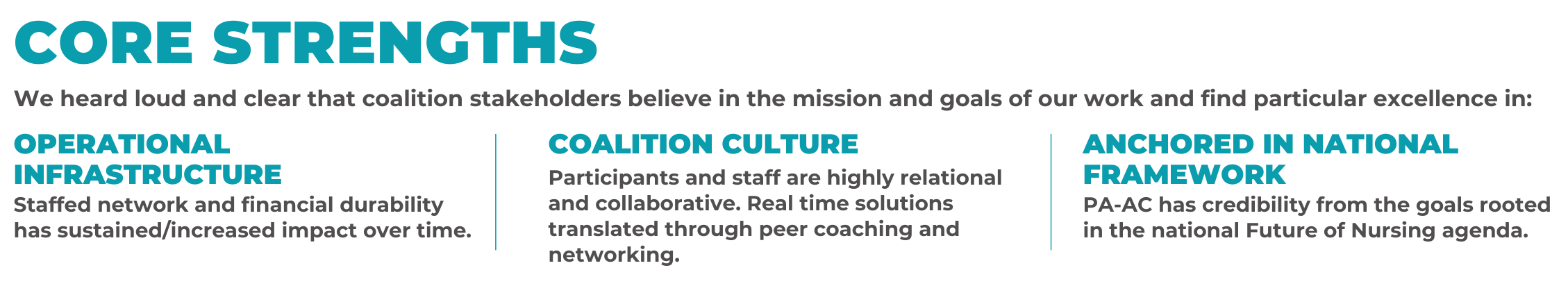

Through this thorough review, it became clear that it would be beneficial to clarify our external role to new and existing stakeholders and to strengthen our position as Pennsylvania’s Nursing Workforce Center. Our feedback expressed that one of our core strengths was our anchor in the national framework of the Future of Nursing’s goals and that our participants continue to feel connected to and inspired by its principles, and there was an increased desire for communications and advocacy efforts. So in approaching our strategic plan, it was imperative to maintain this connection to the Future of Nursing, but we felt it would be helpful for our name to be more reflective of the work that we do to allow us to evolve and expand our external presence.

We are therefore thrilled to announce that effective June 17, 2024, we will be referring to ourselves as the Pennsylvania Nursing Workforce Coalition (PA-NWC) to honor our roots and our future.

OUR VISION: A healthy Pennsylvania through equitable, high quality, and safe nursing.

OUR MISSION: Advancing a nursing workforce that will lead healthcare transformation by cultivating strategic partnerships with diverse populations and organizations.

We are calling this a “brand refresh” and not a “rebrand” because we want to be clear that the components of our structure are not changing.

The PA-NWC will continue to function as a program of the National Nurse-Led Care Consortium (NNCC), operating under the terms of NNCC’s Bylaws, as a Pennsylvania nonprofit corporation, and as a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization.

Further, we will maintain our Advisory Board structure as a coalition with organizations as members and individual representatives.

The Pennsylvania Action Coalition has “housed” the Pennsylvania Nursing Workforce Center since 2016. The “brand refresh” is just making this work more front and center.

We also want to iterate that the PA-NWC is not distancing itself from the Future of Nursing reports nor the Campaign for Action.

Many other nursing workforce centers across the country are simultaneously their own state’s Action Coalition and workforce center and present themselves as their state’s nursing workforce entity if they are not housed within a school of nursing.

Details about our new strategic plan:

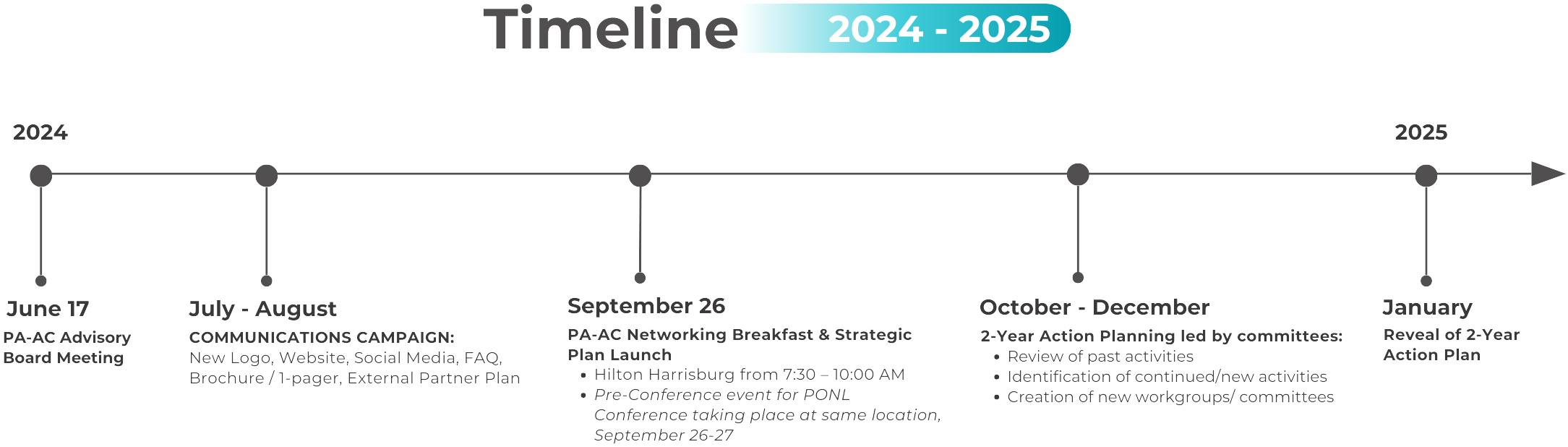

With regards to our implementation plans, we are in the midst of building a communications campaign this summer for our internal and external stakeholders. We plan to develop the following as part of this campaign with a goal of September 26 being our first formal external in-person reveal of our new plan and name:

On September 26, 2024, the Pennsylvania Nursing Workforce Coalition (formerly known as the Pennsylvania Action Coalition) we hosted a successful and engaging breakfast at the 2024 Pennsylvania Organization of Nurse Leaders (PONL) Annual Leadership Conference in Harrisburg, PA. The pre-conference event marked the unveiling of the PA Nursing Workforce Coalition’s (PA-NWC) new strategic plan and the introduction of its key initiatives, aimed at advancing the nursing profession in the state. The breakfast event featured a presentation from our team about the PA-NWC’s new strategic direction. Check out the event recap below!

Content Disclaimer: This episode contains discussions about intimate partner violence that some listeners may find disturbing or difficult to hear.

SARAH: This is At the Core of Care, a podcast where people share their stories about nurses and their creative efforts to better meet the health and healthcare needs of patients, families and communities. I'm Sarah Hexem Hubbard with the Pennsylvania Action Coalition and the Executive Director of the National Nurse-Led Care Consortium. This is the second episode in our two-part series about intimate partner violence. If you haven't heard the first episode, please go back and listen to that one before continuing on. You'll hear from Kalena brown about surviving intimate partner violence and how she's now using her voice to educate and support others.

And on this episode, Lizz Tooher and Mac Taylor will reference Kalena's story as they discuss IPV in Philadelphia and beyond. Mac is a paralegal with help MLP that stands for Health Education and Legal Assistance Project, a Medical Legal Partnership. It's part of Widener University. He works with NNCC on a project that supports families enrolled in home visiting programs across Philadelphia. And Lizz is a public health nurse and senior director of child health and education with NNCC. She works with families raising children ages five and under, through projects including the Mabel Morris Family Home Visit program.

Nurse home visitors go to their clients about twice a month, and they're trained to screen for IPV while there. Through their relationships with clients, they establish enough trust and familiarity to safely support those who screen positive. When that happens, they can turn to Mac one of two recently established IPV champions. Champions can help make plans to leave, secure housing and other resources and navigate legal processes such as obtaining a protection from abuse order or PFA, often working with partner agencies. It's also important to note that we're bringing you these episodes to coincide with mental health awareness month. And as Lizz and Mac discuss, IPV isn't limited to the impact of physical violence on survivors, but very often also manifests psychologically and emotionally, not to mention financially and otherwise. And now we'll go to Lizz to start the conversation.

LIZZ: I'm Lizz Tooher, a public health nurse and senior director of child health and education with the National Nurse-Led Care Consortium here in Philadelphia. I work closely with a number of projects supporting families, specifically raising children under five years old. The primary program I work with is a home visiting program, The Parents as Teachers model and our local program is called the Mabel Morris family home visit program, and we partner with families to support them on achieving their goals for their family, their children. Things like a medical home, safe and reliable place to live and play and work and thrive in Philadelphia. I'm joined today with Mac Taylor, dear colleague, paralegal with NNCC's Health Education and Legal Assistance Project. That is a Medical Legal Partnership or the HELP MLP, as we call it around here.

Today, Mac and I are going to talk about our work supporting survivors of intimate partner violence in Philadelphia area and beyond. First, we want to share a little about how and why we got into this work. For me, being a new nurse home visitor when I was starting my career here about 11 years ago, I think I noticed supporting families with intimate partner violence, the impacts and the effects of that violence on everyone in the family. What I've seen as a home visitor that when home isn't safe, it's hard to focus on any other challenges. When home isn't safe for you, for your children, for any reason, if your home isn't safe, that is really the starting point of my work with a family. How do we get safe housing for you, safe from physical violence and any other aspect. And growing up myself in a home that wasn't always safe, I really connected to wanting to shine a light on this too often unspoken, really epidemic levels of violence happening to families.

As I started working as a home visitor and supporting families living with intimate partner violence, I was so struck by these unhealthy relationships and IPV that it's just so pervasive. And the more I worked as a home visitor, the more I saw that it was a very tangled, broken web of support for families, and I just kept finding myself more and more drawn to this area of support for folks. And I think from there, I've just really been passionate about trying to untangle the systems of support and also lifting the weight off these family shoulders and raising awareness. Really shining the light there to get those agencies to respond to this crisis. Mac, as we said, you’re a paralegal with our Medical Legal Partnership, and you're also an IPV champion. Last year, when we started this champion project you stepped up and applied and were one of two chosen at NNCC. Could you tell us a little about what it means to be an IPV champion and what inspired you to take that step and be involved in this work?

MAC: Thank you, Lizz, for that great introduction. I chose to be an IPV champion because I've been a paralegal going on about eight years now. The first part of my career, I was also a victim advocate, and this is something that is near and dear to my heart. Just being in poverty is trauma and to experience domestic violence and intimate partner violence compounds on that trauma as well. That's where you tend to see IPV and domestic violence, and it shows up in multiple ways, not just physical, mental. There's financial exploitation and the effects that it has on families. So, myself, I've experienced poverty. I've had family members go through domestic violence. So, I believe in a systematic approach, and I believe me taking on this role allows me to be an active participant and not only helping people become whole, but also advocating for change in the system.

LIZZ: Thanks, Mac. So, we should define what we're talking about. What is intimate partner violence? The CDC defines it as abuse or aggression that occurs in a romantic relationship with an intimate partner. Can be current or former spouses. It can be a person of any age or gender. Can vary in how often it happens, how severe it is, and can range from one episode that could have lasting impact to chronic or severe episodes over many years. It can include one or many types of behaviors, several of which we saw in Kalena’s story, the incremental steps of increasingly isolating behavior from the person choosing abuse. The psychological, emotional and financial aspects beyond the physical violence that I think folks might think of first. Mac what do you think of when you think of the definition of IPV or intimate partner violence?

MAC: I try to break it down into simpler terms. A partner tries to make someone do something that they don't want to do. They're unwilling. And it can be a variety of things, and I know what happens is, is that the perpetrators usually use, we call them red flags, but really just some tactics, like they try to isolate them from their family. They become hyper critical of every decision they made. They want to be in control of everything, excessive, like frequently contacting them, and they know they don't want to be contacted. And I've even seen it their financial exploitation. So that's how I would sum it up.

LIZZ: I like that you changed the language a little bit because it's a heavy title, and it's a heavy title to say to a person living in IPV it's also important to note that with the population that we support, fighting poverty during pregnancy, becoming parents, raising young children, those times are just so tumultuous for any parent. There's so many decisions, and who can you trust when you layer on the violence of an intimate partner. It can be so confusing to know what's real and what's not, especially when your home is not a safe place. So, I think IPV is the inability to trust your instincts and to trust yourself. Can we talk a little bit about risk factors? And you started to mention some red flags?

MAC: I see fear. It is not just fear of physical abuse, but the fear of isolation, right? And this is why I value our home visitors so much, because they have those established relationships, and sometimes the home visitor is the only lifeline they can get to. There's so many clients that I've worked with that they didn't even know the state of their financial affairs because the abuser has shut them out of everything, and this is what they deal with every day. They're also parents, and they don't want, nobody wants, to break the American dream of the two-parent household and how does that impact the kids? And oftentimes, they suffer the abuse because they simply don't want to have to abandon their kids or put their kids in a bad situation. And with our home visitors, because they have the interactions with them, they can see these red flags, and then they start to say, I may need to offer them this service. And how can I help them? What can I do to help alleviate some of this victimization.

LIZZ: So, Mac, I know you know that home visitors are very keen on promoting protective factors as a way to mitigate risk factors. We work with families to recognize the strengths that they have, and we work to build up those protective factors. Can we talk a little bit about what protective factors we might be looking for in families to help insulate them from the risks of intimate partner violence?

MAC: I can tell you one of the things when I do a consult with a home visitor, and depending on their assessment, one of the things I always recommend, well, can you arrange to meet the client in the community and take them out of that abusive environment, and then you can have create a safe space where they can be open and honest about what's going on. Most of the clients, they don't know the state of the financial affairs because the abuser has been so controlling. They don't know the electric bill, they don't know the gas bill, they don't know how much money is in the bank account. So I always tell them, you can always recommend your client go to a different bank and set up their own account, and if they don't have the proper documentation, they can also possibly help them acquire that documentation that they would need to open up an account. Sometimes, when people experience domestic violence, they don't even have access to their own vital records, like they can't access their passport, their birth certificate, their social security card. That goes back to that controlling factor. They don't know the terms of their lease. They don't know what's on their credit. The abuser could have been using their credit to acquire things without the victim's acknowledgement or permission. So these are things that all come up as red flags as far as financial stability. And once again, most of the time, survivors are in fight mode. I don't want to be harmed tonight, so I'm gonna do whatever I'm asked to do, whatever I'm told to do, because I don't want to get beat tonight. I don't want to be abused mentally tonight, and if I do this, if I do something wrong, my kids may not be safe. So they don't even think about their selves. They're just thinking about their children.

LIZZ: So definitely the financial stress not being financially independent, or even just financially aware of the state of finances. And then you were talking about the role of community, and I think that's a real place that home visiting looks to support to that peer to peer, community member to community member experience. Whether it's just meeting your home visitor in a park in your neighborhood or the Dunkin Donuts, the library in your area. Or it's coming to an event with other families that are in home visiting or have young children, and these small ways to build community and break down some of this isolation. I think in Kalena’s story, we see some of that too with her own parents and family folks that want to step in or don't know how to step in. So that always brings out, for me, the education of IPV and how do we inform loved ones on how to help one another when these things happen too, and what to look for.

MAC: I agree. And I think, you know, this is such a unique program, because every survivor doesn't have access to a home visitor. So I always looked at as our home visitors on the ground running. And I think just recognizing the small things. For example, if a home visitor has to constantly call the partner to get a hold of the actual client, why is that? Why is it the client doesn't know why the gas got shut off? Are they not able to look at the mail? Do they not have access to the account? Why don't you know how much you have in your bank account? If you're working you have a direct deposit going in, you should be able to have access to it. So I think the home visitors are uniquely positioned. And then two, sometimes the clients have endured it for so long, they normalize it. They don't think anything's wrong, and they had that trusting relationship with their home visitor. A lot of times, the survivor is not in a place to take that first step, and you have to let them get to that point where they're ready to take that first step and then support them. And where it becomes challenging is, is that until they're ready to take that first step, how can you still support them?

LIZZ: Yeah, you brought up some tenets of home visiting. For sure, it takes time to build this relationship, this trust with a family and to sort of be let in. On top of the fact that they're having children and figuring out how to raise their babies, and there are a lot of competing challenges and priorities, and the complexity of leaving is not just one day I decide to leave. The shelters are often full or short term, or you have a history of trauma in the shelter system, or someone you love does and stories you've heard. So I think home visitors are also positioned to provide that support ahead of leaving, to start gathering those documents, to referring to your team Mac, for supporting getting those legal documents, and for making a plan, starting a savings, figuring out what assets you do have and can leverage here and those things can take years to develop.

We heard from Kalena just how critical her relationship with her children's pediatrician ended up being to her feeling seen and heard, supported enough to leave her abuser. And Kalena really pointed to a couple of different times that she was screened. She wasn't always disclosing, but she was always listening to see if the opportunity to disclose was there. It was always in her mind and I recall that even from my own childhood, just kind of that hyper vigilance of who is a safe person, who might have an idea of what's going on when you are in that survival, just kind of always being on alert for those moments and those people. And that's where I see our role with screening and with being the person that creates the space for a person to disclose when they get there, when it's time. So I know there have been more efforts for screening and having the support for when folks do screen positive and disclose there. So more access to resources or IPV champions, such as yourself Mac at these healthcare agencies or emergency rooms, where people might come in and really normalizing it. We've danced around this statistic a little bit, but we haven't come out and said that in North America, homicide is the leading cause of death for pregnant people, and that homicide is linked to IPV and or firearms. so these deaths outnumber obstetric causes, hypertension, sepsis, hemorrhage, the leading causes of obstetric death combined. That is a really important fact that folks also don't know just how prevalent it is in pregnant folks and how vital it is that we are doing more to support these folks and screen and look to our systems to respond to this. So Mac, I know that home visitors will refer to the Help MLP to your legal team, and from there, start working often on the PFA process. Can you tell us what PFA stands for? And well, I know you're a big advocate on PFAs and PFA reform, so would love for you to share that now with us,

MAC: Sure. So before I begin to talk about the PFA as a paralegal, I do have to give this disclosure that I am not an attorney and I cannot give legal advice, but I can speak on a PFA and how that works. A PFA, as is commonly referred to, is a Protection From Abuse order. You can get that in the city and county of Philadelphia. If it's Monday through Friday, you go down to family court and believe it is the either the second or the third floor. And you fill out a bunch of paperwork, and then you wait, and you wait, and then you get called in a to see a judge, and it's called the ex parte hearing, where the judge basically asks questions about what's on the form. It goes on the record, tells about the abuse, and that judge makes a determination if they can give a temporary protection from abuse order or deny it. If they grant it, do they evict the perpetrator out of the home? The judge makes that determination, and in a perfect world, a client will get that temporary PFA and will be scheduled for what we call a full PFA hearing within 10 days. So, I want to just kind of back up about going down to family court and filing for the paperwork.

Now, some organizations do have a navigator there that will help guide the survivor through filling out the paperwork and provide support while they go into the ex parte hearing, but it's a lot. You can go down there and they open at nine. You may not get called before 11 or even after lunch, and it's not a kid friendly place. So if you don't have childcare, and you have to take a child, you have to go through this process about a traumatic event and wait and wait and taking care of a child. You're not permitted to eat inside of the unit while you're filling up paperwork, but you have a child that you need to give a snack to. So you've gotten there, some people have gotten there at 830 to be first or eight o'clock. So now 12 o'clock comes, they want lunch, so they run outside and get something unhealthy to eat one of the carts they come back in. Oh, the judge is at lunch, but he called you a case, or she called your case. We might can get you in this afternoon, and you have to wait all over again, and then once you get that temporary PFA, they have to take that to the local police station, wait to give it to an officer, then sit there at the police district until the officer comes back, saying that they serve the person, and they have to give them a form so then they can take it back to the court. Because if the perpetrator does not get served with it, they can't conduct the hearing. And unfortunately, through the funding limitations, there's no like legal aid organization that goes in for that initial hearing at the temporary level. So, you have a person that is experiencing IPV and domestic violence, they're dealing with that trauma, and based off of our clientele, where most of them are experiencing some level of poverty, which is also a trauma. So they're going in there with double trauma, and now they have to go into a courtroom, which in itself can be intimidating. And so they endure all that, and then they still know that they had to come back to court.

LIZZ: Mac, it sounds like there are so many places in that process where a survivor would give up on top of the reliving of the trauma of whatever brought you to the place that you're ready to file this PFA. The physical pain or emotional pain that came with that, and then having to run around town to at least three different stops at least a day.

MAC: I would agree with you. And the problem is, let's just say the survivor after four o'clock says, I need a PFA. Now, instead of going to family court, they have to go to Criminal Justice Center. Which is even a longer process, and they can get a temporary PFA, but it's only going to be good until the next business day that family court is open, so that may only be 12 hours.

LIZZ: Generally. How long do they last?

MAC: A typical temporary PFA that is acquired in family court, and judge says yes and granted, the full hearing should be scheduled within the 10 day window. Things get rescheduled, things get continued, things get postponed. The biggest problem I see is there wasn't proper service on the defendant. However, it should be heard within 10 days. And it's a regular hearing. You have the survivor, you have the perpetrator, also known as the defendant. They can be represented by counsel. Judge conducts the hearing. Judge renders the decision. He can grant a full PFA for up to 36 months. He can do for six months, and if the burden is not met, he can say no. It's also important to note that when a PFA is issued, temporary or full law requires that firearms be removed from the defendant's possession. They must surrender them to the sheriff's office.

LIZZ: So why bother doing a PFA like, why should I tell you know, survivors to go for it, that it's worth it.

MAC: You know, sometimes I struggle with answering that question myself, but what I do tell clients, this is the first step in trying to regain your independence, and you trying to reclaim safety. But even with a PFA, it's not guaranteed. We all watch the news. You know, person did everything right, went and got a PFA. Unfortunately, the abuser shows up. You call 911, unless there's a gun involved, there's no telling how long it's going to take for the police to respond. And then the police officer comes, you got to have that PFA in your hand. They're not going to go look it up for you. They don't have that kind of time. We all know Philadelphia Police Department is short staffed. They have more violent crime happening. So a survivor will call police. The police will come, but by the time the police get there, the abuser is gone. If they're not witnessing it, that can be a whole other episode, a whole other debate. No, right?

LIZZ: Your team always reminds us, home visitors, that everything in writing, get that paper trail for every issue. Establish a paper trail. Get it in an email, anything, take photos of it. I think of specific populations that are explicitly more vulnerable in these situations, particular communities of marginalized folks. LGBTQIA community has definitely separate risk factors and harm connected with IPV. When you layer on homophobia, lack of inclusiveness in communities for queer people, and persistence of myths and stereotypes about who can be a victim of intimate partner violence. As well as transphobia, compounding the abuse, making queer people much more vulnerable to IPV than general population. I think of recent immigrants, often naturally isolated in different ways through language being in a new country, figuring out how to establish yourself, and IPV is particularly vulnerable then, as well as male survivors.

MAC: It’s underreported. Survivors don't like to talk about it. They don't seek help. When you look at the numbers. Male survivors rarely want to say anything, because one, people don't believe it, like a man can be a survivor of domestic violence, can endure domestic violence. I think it just goes back to the way society perceives men, but it does happen. As a home visiting organization, we do a good job of being able to support all levels of survivors that come to us, and I think that's because we've taken trainings and we all prepared for when it does happen. I wish I can say, in my experience as a victim advocate, prior to coming here, that every organization was like that. We have to continue to promote the organizations that will support survivors of domestic violence, regardless of gender, orientation or religion.

LIZZ: Thank you for that. It bucks up against some outdated stereotypes of IPV too and what an abuser looks like, a person that chooses abuse and what a person that is a survivor of abuse living with the abuse. And male survivors, queer people survivors are great examples of IPV affecting any person. In your nearly a decade of experiences here, have you noticed improvements, even if they might have been temporary, any improvements in any of the aspects of the process or outcomes?

MAC: Yes, we're seeing more people wanting to get involved in the IPV DV fight as an organization, we've really done a lot of training. We've now let our home visitors know that they're fully supported with these type of situations. On the legal side, we continue to look at ways of additional funding. We also maintain some great relationships that can really help our survivors get back to a good way of life. It's not just about a legal issue could be a housing issue. It can be a financial management issue. Having those relationships outside of the legal room can really help a survivor get back to a place of stability.

LIZZ: It’s great to hear that there's more interest. I'd like to think, I'd like to believe that the growing field of home visiting in the country, in Philadelphia the last 10 years also is supporting that push. And Mac I think our project having two IPV champions at NNCC, working with the broader team with the two other home visiting agencies, Maternity Care Coalition and Parent Child Plus, as well as the leadership of CHOP Policy Lab and the funding of Vanguard and the support from Philadelphia's Department of IPV Services and other community stakeholders on this project. The intensive training and the knowledge that you are able to share and empower the team with, I like to believe that these changes are lasting as well. Is there anything else that you can think of that could be effective? Have you heard about anything in your work, policy or other pilot programs like this one.

MAC: I'm hoping to hear some stuff as the new fiscal year goes forward. I'm constantly looking at the Victims of Crime Act funding to see if there's additional funding to expand services. What I will say that is very encouraging. I'm starting to see more diversity in victim services, especially around IPV and DV. I remember years ago, I went to an event, and I was the only man there at the time and a man of color. So, I think as we continue to see diversity in advocates that are helping the survivors of domestic violence, it allows for people to be more comfortable with reporting and seeking help. The numbers tell us that it's happening, but we all know that it's happening at a greater level, because everyone's not reporting. So I think by continuing to do the work we do, we create a space where people can feel safe to report, and we can meet them where they're at and help them navigate through that trauma that they're enduring. So thank you, Lizz, for your leadership on this project and keeping us together, and always having an open door where we can throw ideas and make a change. You know, sometimes just giving someone a burner phone can be life saving, and I can say that we have that available, and it's not a lot of corporate red tape to make it happen.

LIZZ: Thanks, Mac. Yeah, it's great partnering with you too and being able to really give the direct support to our families and our staff.

SARAH: Many thanks to Mac and Lizz for taking the time to share their expertise and perspectives. We would also like to thank our partners at CHOP Policy Lab and Vanguard Strong Start for Kids, for their work to advance precision home visiting. You can find our most current and past episodes of At the Core of Care, wherever you get your podcasts, or at pa action coalition.org. On social media, you can stay up to date with us through our handles at pa action and at nurse-led care. I'm Sarah Hexham Hubbard with the Pennsylvania Action Coalition and the National Nurse-Led Care Consortium. Thanks for joining us so.

Content Disclaimer: This episode contains discussions about intimate partner violence that some listeners may find disturbing or difficult to hear.

SARAH: This is At the Core of Care, a podcast where people share their stories about nurses and their creative efforts to better meet the health and healthcare needs of patients, families and communities. I'm Sarah Hexem Hubbard with the Pennsylvania Action Coalition and the Executive Director of the National Nurse-Led Care Consortium.

This episode begins our two-part series on intimate partner violence, or IPV. You'll hear from Kalena Brown, an IPV survivor who's navigated custody disagreements, endured systemic failures, suffered physical and psychological trauma, and grappled with the societal emotional and financial fallout. Kalena's story, including her perspectives on persistent institutional problems, and efforts to address them, is powerful, and reclaiming her voice to tell it has been hard won.

IPV is prevalent and persistent, though statistics vary depending on several factors, and of course, don't capture the many victims who don't report. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, found that a third of women and a quarter of men report experiencing severe physical violence from an intimate partner. 20% of women and nearly 8% of men report violence, and 14% of women and 5% of men experience stalking.

As you'll learn, IPV isn't limited to the impact of physical violence on survivors, and it's important to note that we're bringing you these episodes during Mental Health Awareness Month. Very often, IPV also manifests psychologically and emotionally, not to mention financially and otherwise.

Before we begin, we want to let you know that this episode contains discussions about intimate partner violence that some listeners might find disturbing or difficult to hear.

KALENA: Hi, my name is Kalena Brown. There are many different titles that people would give me. I'm entrepreneurial. I have an all-organic baby food company. I’ve published three books myself. Two are children's books, one is a devotional, I will definitely say IPV expert for sure. I have spoken on podcasts before. I have done different interviews with different hospitals in Philadelphia. There are organizations that I have come into contract with that I speak with. I've spoken on panels, doctors and different healthcare professionals have asked my opinion in some things that concern health with mothers and giving birth, or domestic violence and relationships prior to giving birth or after birth.

It's been nine years now since I left my abuser, and from the nine years till now, my voice has been something that I now use to help other people get out of situations, whether they think it's abuse or not, where there are certain signs that you may not think is abusive, because they may not specifically harm you physically, but there are other ways that you can be abused that a lot of people aren't aware of, and some of my testimony and story alone is enough that helps them see like, Hey, I did think that this was healthy, and now hearing your story, I realize that it's not.